Asian Grief: 5 Ways My Chinese-American Heritage Influenced My Experience of Grief and Loss Culture, family of origin, race, ethnicity and identity: These are all factors that can shape how we experience grief after loss. I'm a grief coach, and when my mother died, my...

Asian Grief: 5 Ways My Chinese-American Heritage Shaped My Experience of Grief and Loss

Asian Grief: 5 Ways My Chinese-American Heritage Influenced My Experience of Grief and Loss

Culture, family of origin, race, ethnicity and identity: These are all factors that can shape how we experience grief after loss. I’m a grief coach, and when my mother died, my Chinese-American heritage affected my grief journey in unexpected ways.

In this video and post, I share five ways that my Asian heritage has influenced my experience of grief. I discuss the assumptions made about different cultures’ approaches to grief, the norm of not talking about illness and death, the role of superstition and traditions, the expectations of how to grieve, and the multi-layered nature of my grief journey.

Hi, I’m Charlene Lam. I’m a certified grief coach and the founder of The Grief Gallery. I was born in Europe and I grew up in New York City in Chinatown and in the San Francisco Bay Area.

I can only speak for myself and to my own experiences of grief and all the factors that go into that: My family history, the culture of my family of origin, and the larger culture that I grew up in.

I really want to emphasize that because there are a lot of different kinds of Asian-Americans. There are a lot of different kinds of Asians! We are not a monolith. Our cultures can be very different and our individual experiences can be really different. So I just want to speak for myself and my own experience.

Some context for the losses I’ve experienced:

One, my grandmother, she died of cancer when I was five. That was my first experience with understanding what death was. And that wasn’t an easy lesson for reasons I’ll share in a moment.

And then my mother died from a stroke when I was 35 in January 2013. That was the biggest loss that I’ve experienced as an adult.

Here are five ways that my Asian heritage shaped the kind of support that I got and influenced my experience of grief and loss.

1. Assumptions about Grief in Asian and Eastern cultures.

There are a lot of assumptions made about how different cultures experience grief and approach grief and death and loss. I’ve had everyone from friends to strangers to therapists and other grief support people say: “Oh, well, you know, Eastern cultures have such a healthier relationship with death” and “Asian cultures have so many more ways and practices of staying connected to their ancestors.”

That might be true. And as I said, we are not a monolith. We are lots of different kinds of cultures. Eastern culture includes East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia. And there are a lot of different cultures and religions and practices within those regions.

And just because generations and generations ago in China, there might have been practices for staying connected to our ancestors, that doesn’t mean that any of that carried over to my experience growing up as a Chinese-American child or in my practices as an adult.

So that’s one: Assumptions made about what my practices might be, what my family and what my culture’s approach to grief, death, and dying might look like.

2. In my Asian-American family, not talking about illness and death was actually the norm.

Contrary to the popular belief that Eastern cultures are so much better about talking about death and dying and staying in touch with our ancestors and people who have passed on, that absolutely was not my experience.

In fact, it was the opposite. Throughout my childhood and even my adulthood, a lot of information was withheld. When someone was ill, when someone was in trouble, when someone had died, I often would not find out for days, for weeks, or for years.

There might have been a range of reasons for that: I was the youngest child, so sometimes that was to protect me. With my grandmother, my mother didn’t have the language to explain what death meant, that my grandmother was actually gone.

And often there were cultural aspects.

I remember standing with my mom in the lobby of our apartment building after my grandmother died. A neighbor asked, how is my grandmother doing? And my mother said, “She’s fine.” As a five-year-old, I was so confused: What do you mean she’s fine? You’ve just been saying that she’s gone, she’s dead.

Looking back now, I have so much compassion for my mother, for why she said that. My mom tried to explain it to me later, saying she didn’t want the neighbors to gossip, she didn’t want to have to field questions. (After all, she was a grieving daughter herself!)

And as my aunt explained it, often in our culture, there might be aspects of not wanting to bother other people, not wanting to share bad news.

Not talking about illness and death was just the norm in my family of origin. So you can imagine how that influenced my experience of grief and loss, and the idea of getting support, when I was taught:

- Talking about illness and death is unlucky.

- You shouldn’t be talking about it.

- People don’t want to talk about it.

I can only imagine how isolated other members of my family might have felt at different times of loss. Because potentially other people didn’t even know that they had lost a person!

So, that’s number two: Not talking about illness and death was actually the norm. And that leads to …

3. Superstition played a big role in my culture’s approach to grief and loss.

A big reason that my family of origin, my Chinese-American family, did not talk about death and dying was because it was considered unlucky. There were a lot of superstitions that my family members had inherited from their family members and from their culture. And while my parents and immediate family weren’t that traditional, they still held on to some of those superstitions.

For instance, Chinese New Year – the Lunar New Year – is an important time of year culturally. You might know about some of the things that are considered lucky: Red envelopes, oranges, the color red. All considered lucky.

And there are a lot of things that are considered unlucky when it comes to the Chinese New Year, including talking about death and dying.

Unfortunately for me, my mother died shortly before Chinese New Year.

My family members said, “Don’t tell people. It’s unlucky. We don’t want to make them feel uncomfortable heading into the Lunar New Year.”

And these were family members who had been in the U.S. for decades! In a lot of ways were very modern, but they still held on to some of these superstitions. When my uncle was sick a couple of years ago, he didn’t want to go into the hospital. because the Lunar New Year was coming up.

I’ve heard similar accounts from other Chinese friends and colleagues who said, “Yeah, I wasn’t welcome into other people’s homes because I had recently experienced a death.”

Again, you can imagine how isolating that might feel in circumstances that already feel isolating!

Studies show that community support can be so important after we lose a loved one. You can likely see how that role of superstition might have blocked the receiving of that community support.

4. As an Asian-American griever, I felt disconnected from cultural traditions.

Another way that being Asian influenced my experience of grief was feeling disconnected from cultural traditions.

This varies a lot from family to family. Some families are really traditional, and they do practice using an altar, for instance. Maybe their family had Buddhist traditions, and they maintain that. Maybe they went to the cemetery regularly and had rituals and ceremonies.

I personally did not grow up with those traditions. I saw altars in restaurants and businesses when I grew up in Chinatown. I knew that offering fruit and burning incense on those altars were things that were done. But I never understood the meaning or purpose. That was not something that we did in our home, and my parents and family members didn’t really tell me much about it.

Why was this the case? I think as Chinese-American immigrants, my parents emphasized fitting in and assimilating with American culture.

That’s a long tradition of this. Asian-Americans are often cited as the model minority. And that is a myth: the model minority myth. But the belief that fitting in was the way to success was not uncommon for a lot of Chinese immigrant families, and that was certainly the case for my family.

For instance, rather than sending me to Saturday School so that I could learn Chinese along with some of my classmates in Chinatown, my parents didn’t want me to do that. They wanted me to have more of a childhood, an American-style childhood where you had your weekends off. So while I appreciate that, there were definitely aspects of Chinese-ness, my heritage and traditions that they didn’t teach me. As an adult I do feel that disconnect.

There were also expectations about how to grieve: How to grieve in a Chinese way or an Asian way, and how to grieve in an American way. Some family members expected grieving to look like being stoic and being strong. And then some of my more Americanized family members expected me to be more emotional and to cry more after my mother died.

That was another aspect of feeling disconnect — not knowing what was right and not feeling like I knew what was expected of me.

5. Multiple layers of grief and loss as an Asian immigrant.

That brings me to my last point about how being Asian influenced my experience of grief and loss and still continues to: It’s a multi-layered experience. This is true of a lot of grievers, where we keep on peeling the layers of the onion (if you’ve heard that saying). There are these layers and layers that we keep on peeling and finding as we learn more, as we integrate loss into our lives, as we learn to coexist with our grief, even as we move forward with our own lives.

For me, those layers often involve looking at what shaped my family’s responses to death, dying, and grief.

When I was younger, I had a lot of resentment and judgment for how they responded. I had a lot of judgment about family members withholding information, or trying to protect me by making sure I was being more American than Chinese.

Over the years, especially in more recent years, I’ve been peeling back layers of why they did that, and I have so much more understanding and compassion for them.

Often it came back to a matter of survival. Either for economic survival, and sometimes for their actual survival.

The aspects of lying and telling half-truths that I encountered were so confounding when I was little. Growing up in the U.S., I learned in elementary school that you shouldn’t lie, that you should always tell the truth. It did not make any sense to me why my family members would withhold information, and why they would lie about some of these hard truths.

As I got older, and as I learned about things like the Cultural Revolution in China and discriminatory immigration laws in the U.S., I came to understand that a lot of my Chinese-American heritage involved necessary lying.

Survival involved telling half-truths, masking and not telling the full story, whether that was because U.S. immigration laws said that Chinese men could not bring their families. Or whether it was because I had relatives who lived through the Cultural Revolution in China, and they brought the impact of that trauma over when they immigrated to the United States.

There are so many layers that I’m still unpeeling. More recently, I was reading about the history of New York’s Chinatown, and why Chinatowns formed. I read that Chinatowns were built as a form of protection because of attacks on Chinese immigrants in the larger society. And it had never struck me that was a reason why Chinatowns would form, and why Chinatowns would be so insular, and why they kept to themselves.

There are layers of grief associated with all of that — layers of loss and layers of me trying to better understand relatives that I’ve never met or don’t remember.

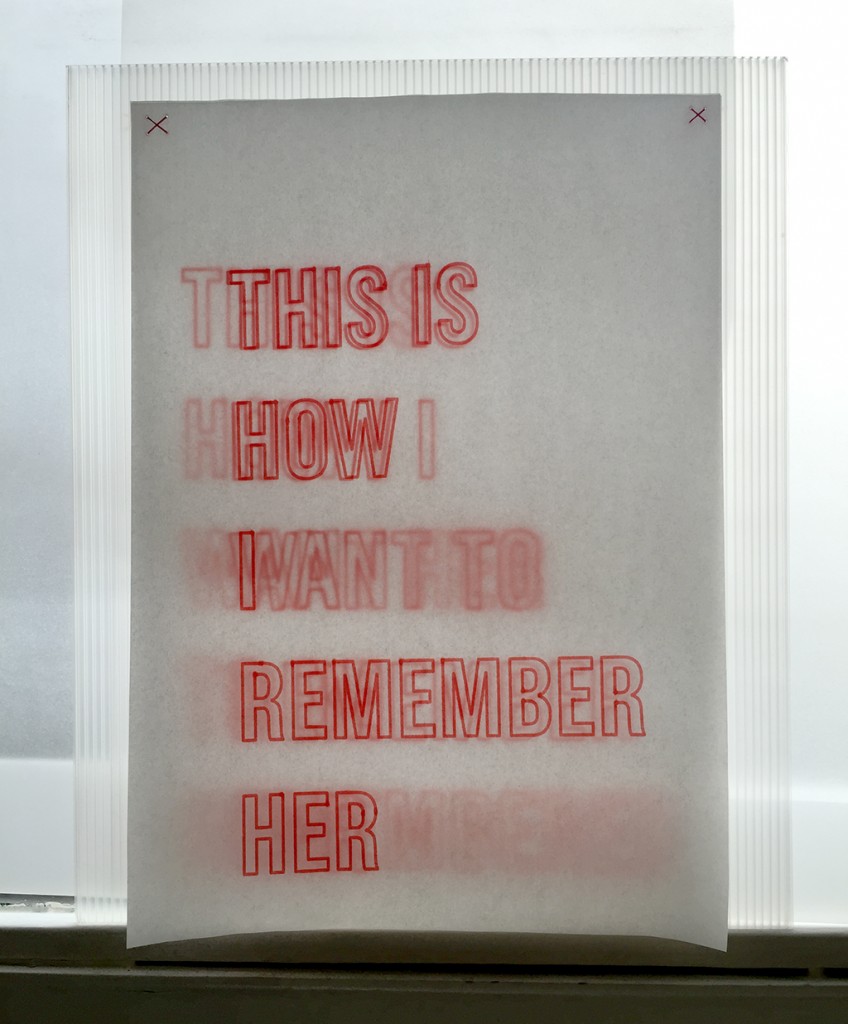

I recently cleared out my family’s storage unit, and I found photos of my grandfather and my grandmother.

My grandfather died when I was three. He got cancer and did not tell anyone about the symptoms until it was too late — which is not uncommon for men of a certain age or generation. But again, that was the story of my family’s life, not telling things.

My grandmother died when I was five, so I don’t really remember her.

I think: What layers of loss and grief did they carry? Did they actually have any kind of opportunity to address their grief? And what were they taught?

I’m still peeling back the layers.

Thanks for learning a bit about my stories of Asian grief and loss. Again, I can only speak to my own experience as a Chinese-American, as someone who grew up in New York, in the San Francisco Bay Area, and who grew up in my particular family, in our particular society.

But I hope that gives you some ideas of the different ways that being Asian might influence someone’s experience of grief and loss.

I’d love to hear from you — how have your culture, heritage and family of origin impacted your experiences of grief and loss? Connect with me on Instagram @curating_grief or attend The Grief Gallery’s free monthly gathering.

Want help unpeeling the layers of your own experience of grief and loss? Find out more about working with me and my Unpacking Grief coaching package.

hello

I'm Charlene

I help grieving people feeling burdened by responsibilities, resentments and regrets after the death of a loved one to feel lighter –– so you can live your own fullest life.

After the sudden death of my mother Marilyn in 2013, I put my life, work and grief on hold as I struggled to deal with the estate, paperwork and belongings.

Healing took time -- and it took help.

I'm a certified grief coach, and I developed my Curating Grief framework to help people process grief in a creative, accessible way. Learn how to move forward, without leaving your connection to your loved one behind.

Get In Touch

- hello@charlenelam.com

CONTACT

- hello@charlenelam.com

CONNECT

YOU ARE ALL WELCOME

WORK WITH ME

GRIEF COACHING

MEET ME IN LISBON

SPEAKING AND WORKSHOPS

MONTHLY GRIEF GATHERING

Join us for The Grief Gallery's free, supportive grief group gathering the last Wednesday of the month, 2pm ET (7pm UK).

CURATING GRIEF PODCAST

- Listen to the Curating Grief podcast

GRIEF RESOURCES

Need help with grief? I can help.

Get in touch: Email hello [at] charlenelam.com

Note: Coaching and coaching consultations are not a substitute for counseling, psychotherapy, psychoanalysis, mental health care, substance abuse treatment, or other professional advice by legal, medical or other qualified professionals. If you are experiencing a mental health emergency, contact 911 or your local emergency services.

Copyright © 2023 Charlene Lam. Curating Grief ™ and The Grief Gallery ™. All Rights Reserved | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy